25 Normality tests

Tests of normality are statistical inference procedures designed to test that the underlying distribution of a random variable is normally distributed. There is a long history of these tests, and there are a plethora of them available for use, i.e. Jarque and Bera (1980), D’Agostino and Pearson (1973), Ralph B. D’agostino and Jr. (1990). Such kind of tests are based on the comparison of the sample skewness and kurtosis with the skewness and kurtosis of a normal distribution, hence their estimation is crucial.

Proposition 25.1 (\(\color{magenta}{\textbf{Jarque-Brera test}}\))

Let’s consider an IID Gaussian sample with unknown means \(\mu\) and unknown variance \(\sigma^2\), i.e. \[

\mathbf{X}_{n} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma^2)

\text{,}

\] Standardizing the skewness and kurtosis under \[

\mathcal{H}_0: \beta_1(\mathbf{X}_n) = 0, \, \beta_2(\mathbf{X}_n) = 3 \text{,}

\] we have that asymptotically \[

\begin{aligned}

{} & Z_1(\mathbf{X}_n) = \sqrt{n} \frac{b_1(\mathbf{X}_n)}{\sqrt{6}} && \underset{n \to \infty}{\overset{\text{d}}{\longrightarrow}} \mathcal{N}\left(0, 1\right) \text{,} \\

& Z_2(\mathbf{X}_n) = \sqrt{n} \frac{b_2(\mathbf{X}_n)-3}{\sqrt{24}} && \underset{n \to \infty}{\overset{\text{d}}{\longrightarrow}} \mathcal{N}\left(0, 1\right) \text{,}

\end{aligned}

\tag{25.1}\] where \(b_1\) reads as in Equation 10.12, \(b_2\) as in Equation 10.16 and it is possible to prove that the statistics \(Z_1(\mathbf{X}_n)\) and \(Z_2(\mathbf{X}_n)\) are independent.

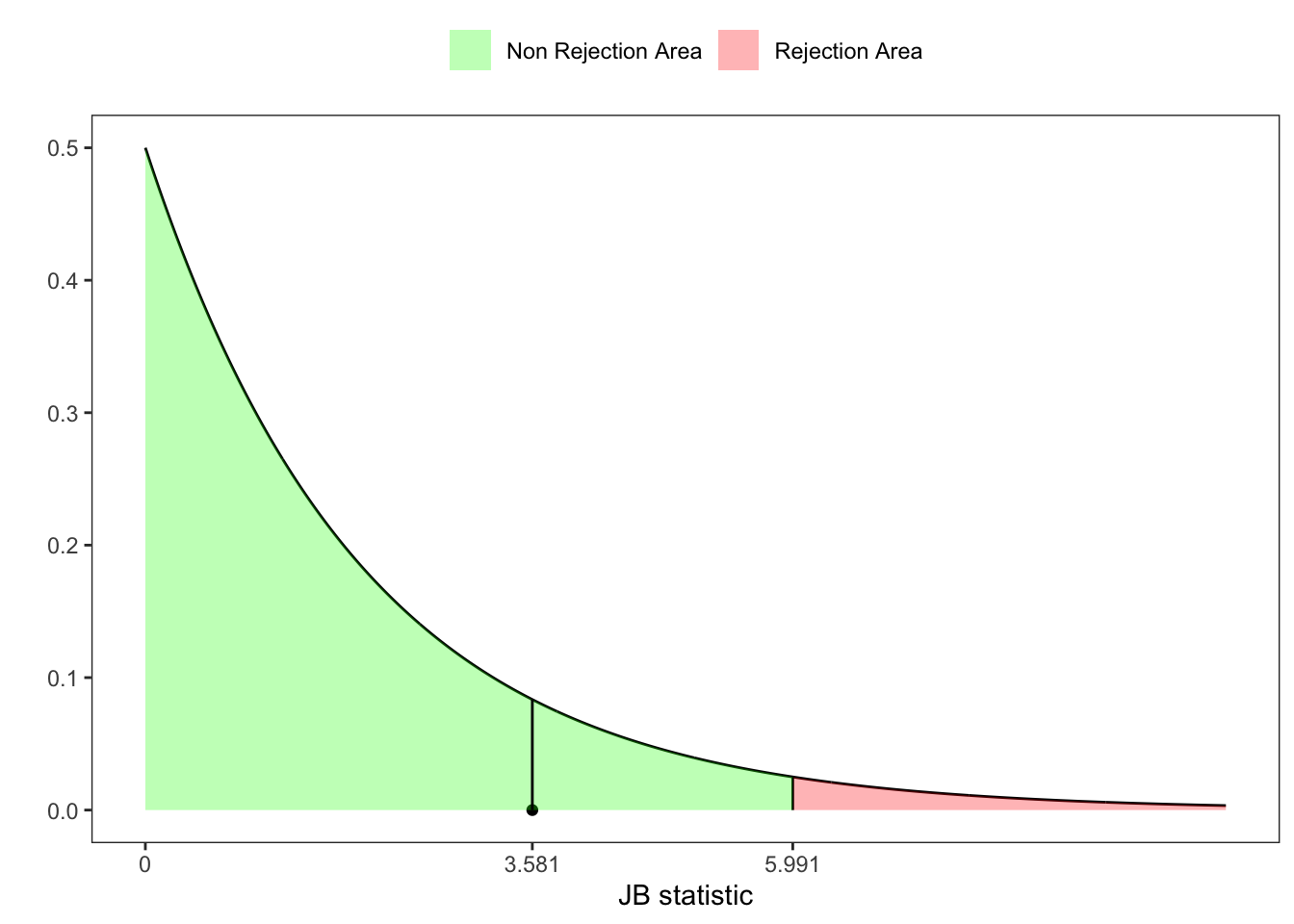

Hence, since the sum of two independent standard normal squared random variables follows a \(\chi^{2}(2)\) distribution with 2 degrees of freedom, the Jarque-Brera statistic is obtained as \[ \text{JB}(\mathbf{X}_n) = Z_1(\mathbf{X}_n)^2 + Z_2(\mathbf{X}_n)^2 \underset{n \to \infty}{\overset{\text{d}}{\longrightarrow}} \chi^{2}(2) \text{.} \]

However, if \(n\) is small the \(\text{JB}(\mathbf{X}_n)\) over-reject the null hypothesis \(\mathcal{H}_0\), i.e. type I error.

Example 25.1

Jarque-Brera test

# =============== Setups ===============

n <- 50 # number of simulations

set.seed(1) # random seed

ci <- 0.05 # confidence level

# ======================================

# Simulated variable

x <- rnorm(n, 0, 1)

# Sample skewness

b1 <- skewness(x)

# Sample kurtosis

b2 <- kurtosis(x, excess = F)

# JB-statistic test

JB <- n*(b1^2/6 + (b2 - 3)^2/24)

# JB-test p-value

pvalue <- 1 - pchisq(JB, df = 2)

# JB-test critic value at 95%

z_lim <- qchisq(1-ci, 2)

Proposition 25.2 (\(\color{magenta}{\textbf{Urzua-Jarque-Brera test}}\))

Substituting in the JB-statistics from Equation 25.1 the exact sample moments of the skewness and kurtosis of a Normal sample instead the asymptotic moments, one obtain the UJB-test (see Urzúa (1996)), i.e. \[

\begin{aligned}

{} & \tilde{Z}_1(\mathbf{X}_n) = \frac{b_1(\mathbf{X}_n)}{\sqrt{\mathbb{V}\{b_1(\mathbf{X}_n)\}}}

&& \underset{n \to \infty}{\overset{\text{d}}{\longrightarrow}} \mathcal{N}\left(0, 1\right) \text{,} \\

& \tilde{Z}_2(\mathbf{X}_n) = \frac{b_2(\mathbf{X}_n) - \mathbb{E}\{b_2(\mathbf{X}_n)\}}{\sqrt{\mathbb{V}\{b_2(\mathbf{X}_n)\}}}

&& \underset{n \to \infty}{\overset{\text{d}}{\longrightarrow}} \mathcal{N}\left(0, 1\right) \text{,}

\end{aligned}

\tag{25.2}\] where the exact moments \(\mathbb{V}\{b_1(\mathbf{X}_n)\}\) (Equation 10.14), \(\mathbb{E}\{b_2(\mathbf{X}_n)\}\) (Equation 10.18) and \(\mathbb{V}\{b_2(\mathbf{X}_n)\}\) (Equation 10.19).

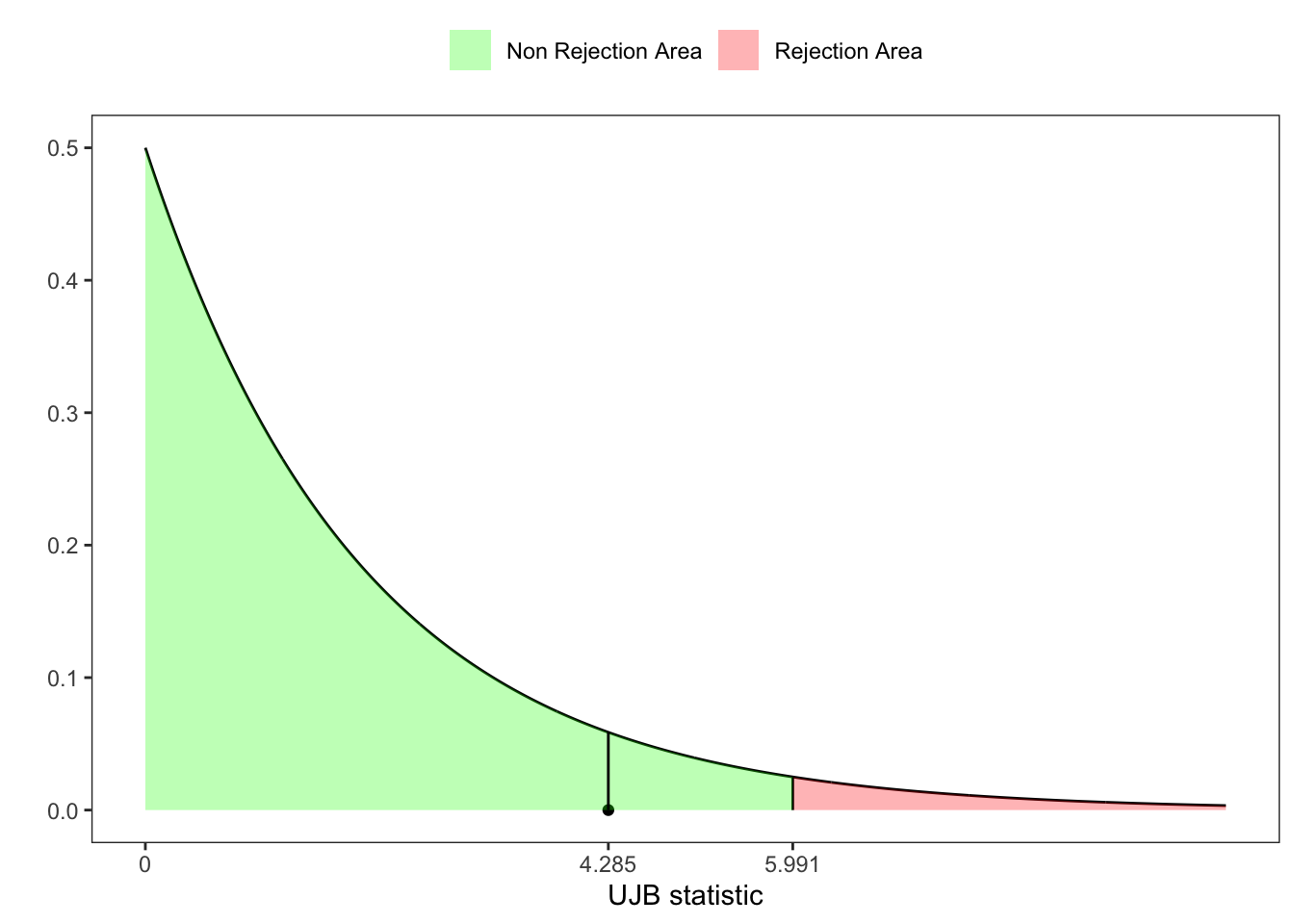

Hence, the Urzua-Jarque-Brera statistic adjusted for small samples is distributed asymptotically as a \(\chi^2(2)\), i.e. \[ \text{UJB}(\mathbf{X}_n) = \tilde{Z}_1(\mathbf{X}_n)^2 + \tilde{Z}_2(\mathbf{X}_n)^2 \underset{n \to \infty}{\overset{\text{d}}{\longrightarrow}} \chi^{2}(2) \text{.} \]

Example 25.2

Urzua-Jarque-Brera test

# =============== Setups ===============

n <- 50 # number of simulations

set.seed(1) # random seed

ci <- 0.05 # confidence level

# ======================================

# Simulated variable

x <- rnorm(n, 0, 1)

# Sample skewness

b1 <- skewness(x)

# Skewness's variance

v_b1 <- (6*(n-2))/((n+1)*(n+3))

# Statistic for skewness

Z1 <- b1/sqrt(v_b1)

# Sample kurtosis

b2 <- kurtosis(x, excess = F)

# Kurtosis's expected value

e_b2 <- (3*(n-1))/(n+1)

# Kurtosis's variance

v_b2 <- (24*n*(n-2)*(n-3))/((n+1)^2*(n+3)*(n+5))

# Statistic for kurtosis

Z2 <- (b2-e_b2)/sqrt(v_b2)

# UJB-statistic test

UJB <- Z1^2 + Z2^2

# UJB p-value

pvalue <- 1 - pchisq(UJB, df = 2)

# UJB critic value at 95%

z_lim <- qchisq(1-ci, 2)

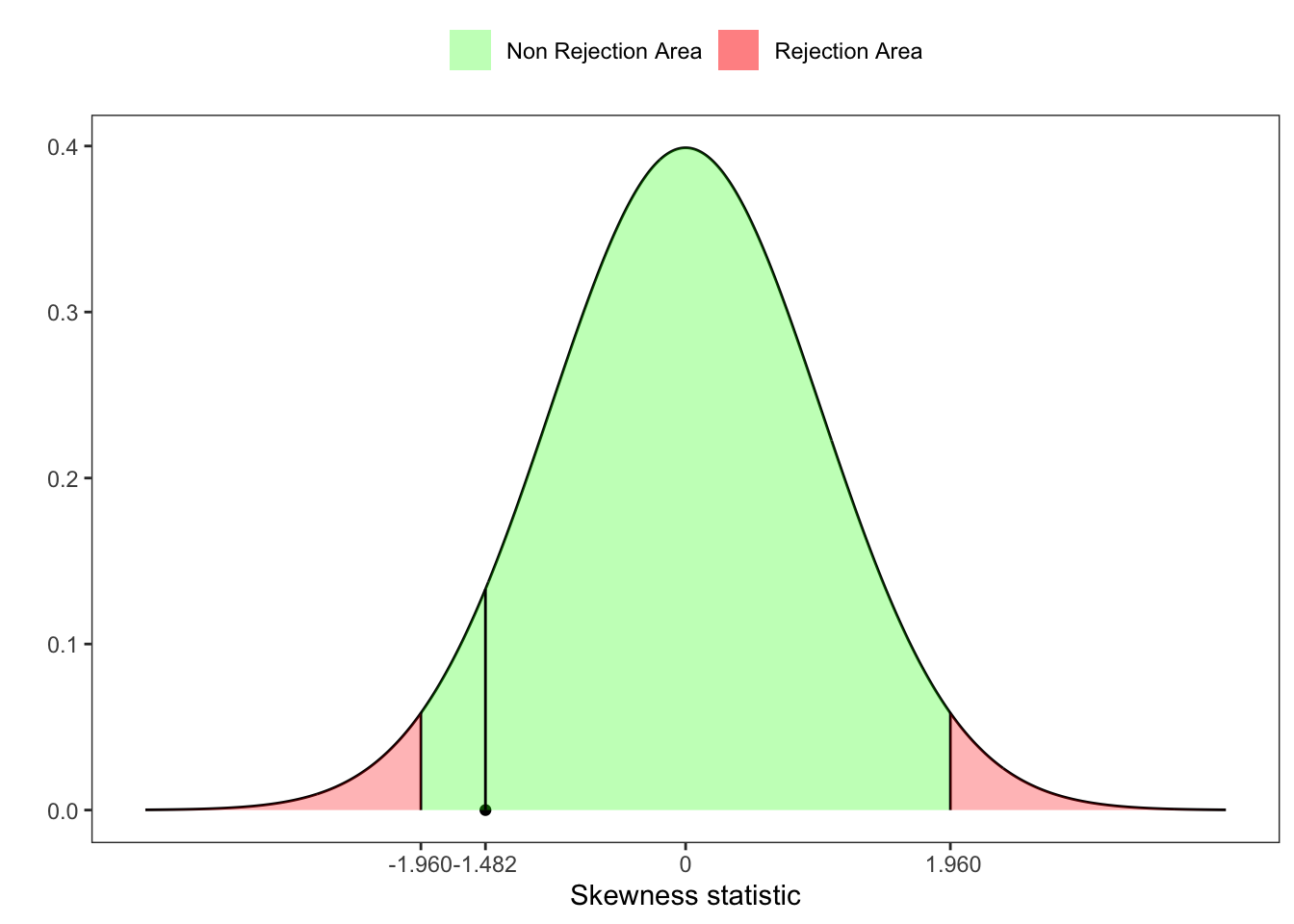

25.1 D’Agostino skewness test

Starting from the statistic \(\tilde{Z}_1(\mathbf{X}_n)\) (Equation 25.2), let’s compute the fourth standardized moment of \(b_1\), i.e. \[ \beta_2(b_1) = \frac{3 (n^2 + 27n -70)(n+1)(n+3)}{(n-2)(n+5)(n+7)(n+9)} \text{,} \] Then, D’Agostino and Pearson (1973) proposed a statistic test for the skewness, defined as \[ Z_1^{\ast}(\mathbf{X}_n) = \delta \log \left\{\frac{\tilde{Z}_1(\mathbf{X}_n)}{\alpha} + \sqrt{\left(\frac{\tilde{Z}_1(\mathbf{X}_n)}{\alpha}\right)^2 + 1}\right\} \tag{25.3}\] where \[ \begin{aligned} {} & W^2 = \sqrt{2 \beta_2(b_1) - 1 } -1 \text{,} \\ & \delta = \frac{1}{\sqrt{\ln(W)}} \text{,} \\ & \alpha = \sqrt{\frac{2}{W^2 - 1}} \text{,} \end{aligned} \] and \(Z_1^{\ast}(\mathbf{X}_n) \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\). Notably, a more compact and equivalent expression reads \[ Z_1^{\ast}(\mathbf{X}_n) = \delta \sinh^{-1}\left( \frac{\tilde{Z}_1(\mathbf{X}_n)}{\alpha}\right) \text{.} \]

Example 25.3

D’Agostino skewness test

# =============== Setups ===============

n <- 20 # number of simulations

set.seed(1) # random seed

ci <- 0.05 # confidence level

# ======================================

# Simulated variable

x <- rnorm(n, 0, 1)

# Sample skewness

b1 <- skewness(x)

# Skewness's variance

v_b1 <- (6*(n-2))/((n+1)*(n+3))

# Statistic for skewness

Z1 <- b1/sqrt(v_b1)

# Test for Skewness

beta2_b1 <- (3*(n^2 + 27*n - 70)*(n+1)*(n+3))/((n-2)*(n+5)*(n+7)*(n+9))

W2 <- sqrt(2*beta2_b1 - 1) - 1

delta <- 1/sqrt(log(sqrt(W2)))

alpha <- sqrt(2/(W2 - 1))

# Test for skewness

Z_ast_b1 <- delta*asinh(Z1/alpha)

# UJB p-value

pvalue <- 1 - pnorm(Z_ast_b1, lower.tail = TRUE)

# UJB critic value at 95%

z_lim <- qnorm(1-ci/2)

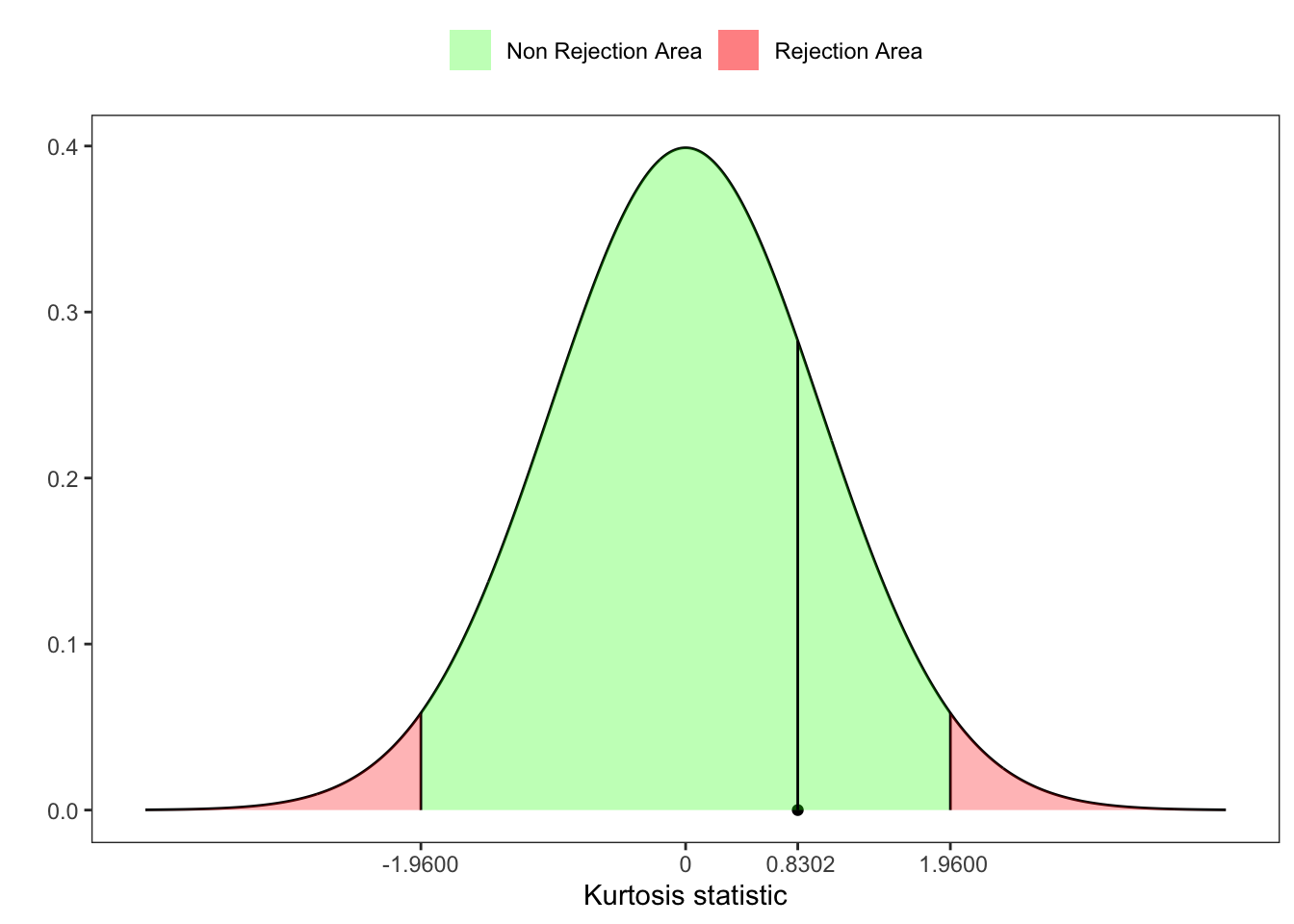

25.2 Anscombe Kurtosis test

Starting from the statistic \(\tilde{Z}_2(\mathbf{X}_n)\) (Equation 25.2), let’s compute the third standardized moment of \(b_2\): \[ \beta_1(b_2) = \frac{6(n^2 - 5n + 2)}{(n+7)(n+9)}\sqrt{\frac{6(n+3)(n+5)}{n(n-2)(n-3)}} \text{,} \] Then, Anscombe and Glynn (1983) proposed a statistic test for the kurtosis, defined as \[ Z_2^{\ast}(\mathbf{X}_n) = \sqrt{\frac{9A}{2}}\left(1 - \frac{2}{9A} - \left[\frac{1 - 2/A}{1 + \tilde{Z}_2(\mathbf{X}_n) \sqrt{2/(A - 4)} } \right]^{1/3} \right) \text{,} \tag{25.4}\] where \[ A = 6 + \frac{8}{\beta_1(b_2)} \left[\frac{2}{\beta_1(b_2)} + \sqrt{1 + \frac{4}{\beta_1(b_2)}}\right] \text{,} \] and \(Z_2^{\ast}(\mathbf{X}_n) \sim \mathcal{N}(0,1)\).

Example 25.4

Anscombe kurtosis test

# =============== Setups ===============

n <- 50 # number of simulations

set.seed(1) # random seed

ci <- 0.05 # confidence level

# ======================================

# Simulated variable

x <- rnorm(n, 0, 1)

# Sample kurtosis

b2 <- kurtosis(x, excess = F)

# Kurtosis's expected value

e_b2 <- (3*(n-1))/(n+1)

# Kurtosis's variance

v_b2 <- (24*n*(n-2)*(n-3))/((n+1)^2*(n+3)*(n+5))

# Statistic for kurtosis

Z2 <- (b2-e_b2)/sqrt(v_b2)

# Test for Skewness

beta1_b2 <- (6*(n^2 - 5*n + 2))/((n+7)*(n+9))*sqrt((6*(n+3)*(n+5))/(n*(n-2)*(n-3)))

A <- 6 + (8/beta1_b2)*(2/beta1_b2 + sqrt(1 + 4/(beta1_b2^2)))

# Test for kurtosis

Z_ast_b2 <- sqrt((9*A)/2) *(1 - 2/(9*A) - ((1 - 2/A)/(1 + Z2*sqrt(2/(A-4))))^(1/3))

# p-value

pvalue <- 1 - pnorm(Z_ast_b2, lower.tail = TRUE)

# UJB critic value at 95%

z_lim <- qnorm(1-ci/2)

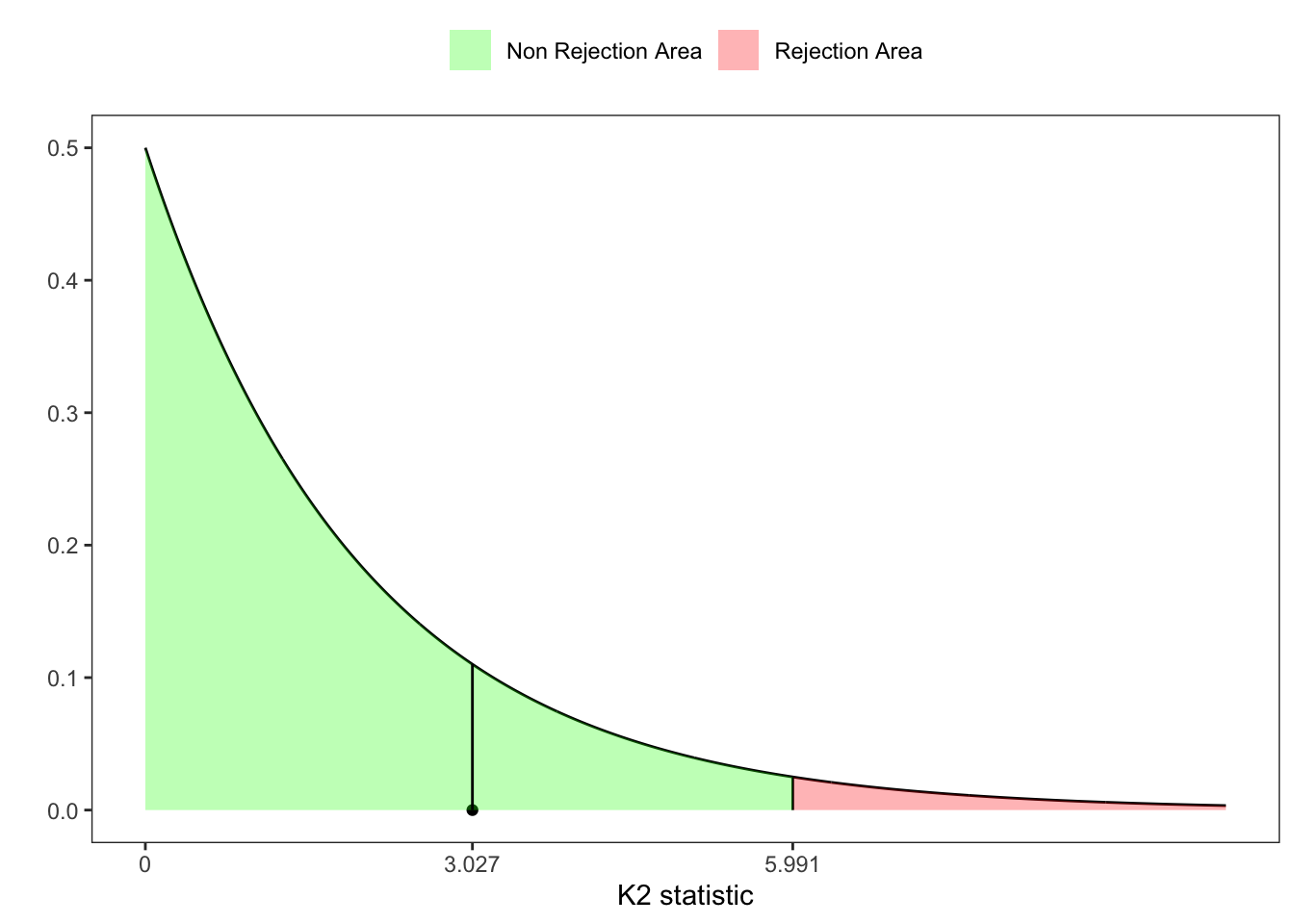

25.3 D’Agostino-Pearson \(K^2\) test

Following a same idea as in JB and UJB test, Ralph B. D’agostino and Jr. (1990) proposed an alternative omnibus test for Normality based on the statistics \(Z_1^{\ast}(\mathbf{X}_n)\) (Equation 25.3) and \(Z_2^{\ast}(\mathbf{X}_n)\) (Equation 25.4), i.e. \[ \text{K}^2(\mathbf{X}_n) = (Z_1^{\ast}(\mathbf{X}_n))^2 + (Z_2^{\ast}(\mathbf{X}_n))^2 \sim \chi^2(2) \text{.} \]

25.4 Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test can be used to verify whether a samples is drawn from a reference distribution. In the case of q sample with dimension \(n\), the KS statistic is defined as: \[ \text{KS}_{n} = \underset{\forall x}{\sup}|\hat{F}_{\mathbf{X}_n} - F(x)| \text{,} \tag{25.5}\] where \(\hat{F}_n\) denotes the empirical distribution (Equation 23.4). The test statistic \(\text{KS}_{n}\) follows the Kolmogorov distribution \(F_{\text{KS}}\) defined as follows \[ F_{\text{KS}}(\sqrt{n}\cdot \text{KS}_{n} < x) = 1 - 2 \sum_{k = 1}^{\infty} (-1)^{k-1} e^{-2k^2x^2} \text{.} \]

Kolmogorov distribution

# Infinite sum function

# k: approximation for infinity

inf_sum <- function(x, k = 100){

isum <- 0

for(i in 1:k){

isum <- isum + 2*(-1)^(i-1)*exp(-2*(x^2)*(i^2))

}

isum

}

# Kolmogorov distribution function

pks <- function(x, k = 100){

p <- c()

for(i in 1:length(x)){

p[i] <- 1-inf_sum(x[i], k = k)

}

p

}

# Kolmogorov quantile function

qks <- function(p, k = 100){

loss <- function(x, p){

(pks(x, k = k) - p)^2

}

x <- c()

for(i in 1:length(p)){

x[i] <- optim(par = 2, method = "Brent", lower = 0, upper = 10, fn = loss, p = p[i])$par

}

x

}The null distribution of this statistic is calculated under the null hypothesis that the sample is drawn from the reference distribution \(F\), i.e. \[ \begin{aligned} {} & \mathcal{H}_0: \hat{F}_{\mathbf{X}_n}(X) = F(X) \text{,} \\ & \mathcal{H}_1: \hat{F}_{\mathbf{X}_n}(X) \neq F(X) \text{.} \end{aligned} \] On large samples, \(\mathcal{H}_0\) is rejected at a given confidence level \(\alpha\) if: \[ \sqrt{n} \cdot \text{KS}_{n} > F_{KS}^{-1}(F_{\text{KS}}(\sqrt{n} \cdot \text{KS}_{n} < q_{\alpha})) \text{,} \] where \(q_{\alpha}\) represents the critical value and \(F_{\text{KS}}^{-1}\) the quantile function of the Kolmogorov distribution.

Example 25.6 Let’s simulate 500 observations of a stationary normal random variable, i.e. \(\mathbf{X}_n \sim \mathcal{N}(0.2, 1)\).

| \(n\) | \(\alpha\) | \(\text{KS}_{n}\) | \(\textbf{Critical Level}\) | \(\mathcal{H}_0\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5000 | 5% | 0.8651 | 1.358 | Non-Rejected |

Kolmogorov test (normal)

# ================== Setups ==================

set.seed(1) # random seed

n <- 5000 # number of simulations

k <- 1000 # index for Kolmogorov cdf approx

ci <- 0.05 # confidence level (alpha)

# ===========================================

# Simulated stationary sample

x <- rnorm(n, 0.2, 1)

# Set the interval values for upper and lower band

grid <- seq(quantile(x, 0.015), quantile(x, 0.985), 0.01)

# Empirical cdf

cdf <- ecdf(x)

# Compute the KS-statistic

ks_stat <- sqrt(n)*max(abs(cdf(grid) - pnorm(grid, mean = 0.2)))

# Compute the rejection level

rejection_lev <- qks(1-ci, k = k)- 1

- Simulated stationary sample

- 2

- Set the interval values for upper and lower band. This is done to avoid including outliers, however it is possible to use also the minimum and maximum.

- 3

- Empirical cdf

- 4

- Compute the KS-statistic as in Equation 25.5.

- 5

-

Compute the rejection level

Example 25.7 Let’s simulate 500 observations of a stationary t-student random variable with increasing degrees of freedom \(\nu\), i.e. \(\mathbf{X}_n \sim \mathcal{t}(\nu)\). Then, we compare the obtained result with a standard normal random variable, i.e. \(\mathcal{N}(0,1)\). It is known that increasing the degrees of freedom of a student-t imply the convergence to a standard normal. Hence, we expect that from a certain \(\nu\) awards the null hypothesis will be no more rejected.

Kolmogorov test (normal vs student-t)

# ================== Setups ==================

seed <- 1 # random seed

n <- 5000 # number of simulations

k <- 1000 # index for Kolmogorov cdf approx

ci <- 0.05 # confidence level (alpha)

# grid for student-t degrees of freedom

nu <- c(1,5,10,15,20,30)

# ===========================================

kabs <- list()

for(v in nu){

set.seed(seed)

# Simulated stationary sample

x <- rt(n, df = v)

# Set the interval values for upper and lower band

grid <- seq(quantile(x, 0.015), quantile(x, 0.985), 0.01)

# Empirical cdf

cdf <- ecdf(x)

# Compute the KS-statistic

ks_stat <- sqrt(n)*max(abs(cdf(grid) - pnorm(grid, mean = 0, sd = 1)))

# Compute the rejection level

rejection_lev <- qks(1-ci, k = k)

kabs[[v]] <- dplyr::tibble(nu = v,

n = n,

alpha = paste0(format(ci*100, digits = 3), "%"),

KS = ks_stat,

rej_lev = rejection_lev,

H0 = ifelse(KS > rej_lev, "Rejected", "Non-Rejected")

)

}| \(\nu\) | \(n\) | \(\alpha\) | \(\text{KS}_{n}\) | \(\textbf{Critical Level}\) | \(\mathcal{H}_0\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5000 | 5% | 9.356 | 1.358 | Rejected |

| 5 | 5000 | 5% | 2.974 | 1.358 | Rejected |

| 10 | 5000 | 5% | 1.751 | 1.358 | Rejected |

| 15 | 5000 | 5% | 1.462 | 1.358 | Rejected |

| 20 | 5000 | 5% | 1.285 | 1.358 | Non-Rejected |

| 30 | 5000 | 5% | 1.190 | 1.358 | Non-Rejected |