Reference: Chapter 5. Resnick (2005).

The expectation represents a central value of a random variable and has a measure theory counterpart as a Lebesgue-Stieltjes integral of with respect to a (probability) measure . This kind of integration is defined in steps. First it is shown the integration of simple functions and then extended to more general random variables.

Let’s define a probability space and a generic random variable such that where . Then, the expectation of is denoted as: as the Lebesgue-Stieltjes integral of with respect to the (probability) measure .

Simple functions

Let’s start from the definition of the expectation for a restricted class of random variables called simple functions. Generally speaking, a random variable is called simple if it has a finite range.

Formally, let’s consider a probability space and a -measurable simple function defined as follows where and is a disjoint partition of the sample space, i.e. .

Let’s denote the set of all simple functions on as . In this settings, is a vector space, that satisfies three main properties.

Constant: given a simple function , then . In fact: where .

Linearity: given two simple function , then . In fact: where the sequence of sets form a disjoint partition of .

Product: given two simple function , then . In fact:

Expectation of simple functions

The expectation of a simple function is defined as: where .

Expectation of an indicator function: we have that

Non-negativity: If and then

Linearity: the expectation of simple function is linear, i.e.

Monotonicity: the expectation of simple function is monotone on , in the sense that if two random variables are such that , then

Continuity: the expectation of simple function is continuous on , in the sense that, if and either or , then

Proof. Let’s consider two simple functions, i.e. and let’s fix . Then, by the second property of the vector space (Equation 5.3) it is possible to write: Then, taking the expectation on both sides:

Fixing , the sequence for is composed by disjoint events since by definition are disjoint. Hence, applying -additivity it is possible to write: Therefore, the expectation simplifies in:

Extension of the definition

Simple functions are the building blocks in the definition of the expectation in terms of Lebesgue-Stieltjes integral. In fact a known theorem called Measurability theorem shows that any measurable function can be approximated by a sequence of simple functions.

Theorem 5.1 ()

Suppose that for all . Then, is measurable if and only if there exists simple functions and

Non-negative random variables

We now extend the definition of the expectation to a broader class of random variables. Let’s define the set as the set of non-negative simple functions and define: to be the set of non-negative and measurable functions with domain .

If , then the expectation and by Theorem 5.1 we can find an such that . Since the expectation operator preserves monotonicity, also the sequence is non-decreasing. Thus, since the limit of monotone sequences always exists, then thus extending the definition of expectation from to .

Integrable random variables

Finally, we extend the definition of expectation to all random variables such that . For any random variable , let’s call Therefore, Then, we define a new random variable that is -measurable if both and are measurable. If at least one among or is finite, then we define and we call quasi integrable. Instead, if both and , then and we call integrable. In this case, we write , where stands for the set of integrable random variables with first moment finite, i.e. In general, writing , means that belong to the set of integrable random variables with -moment finite, i.e.

General definition

The expectation of a random variable is it’s first moment, also called statistical average. In general, it is denoted as . Let’s consider a discrete random variable with distribution function . Then, the expectation of is the weighted average between all the possible -states that the random variable can assume by it’s respective probability of occurrence, i.e. that is exactly the Equation 5.5. In continuous case, i.e. when takes values in and admits a density function , the expectation is computed as an integral, i.e.

Definition 5.1 ()

For any random variable , let’s define the moment of order as: Similarly, for we define the central moment as

Variance and Covariance

In general the variance of a random variable in population defined as the second central moment (Equation 5.9):

Let’s consider a discrete random variable with distribution function . Then the variance of is the weighted average between all the possible -centered and squared states that the random variable can assume by it’s respective probability of occurrence, i.e. In the continuous case, i.e. when admits a density function and takes values in , the expectation is computed as:

Let’s consider two random variables and . Then, in general their covariance is defined as:

In the discrete case where and have a joint distribution , their covariance is defined as: In the continuous case, if the joint distribution of and admits a density function the covariance is computed as:

Proposition 5.1 ()

There are several properties connected to the variance.

The variance can be computed in terms of the second and first moment of , i.e.

The variance is invariant with respect to the addition of a constant , i.e.

The variance scales upon multiplication with a constant , i.e.

The variance of the sum of two correlated random variables is computed as:

The covariance can be expressed as:

The covariance scales upon multiplication with a constant and , i.e.

Proof. The property 1. (Equation 5.12) follows easily developing the definition of variance, i.e. The property 2. (Equation 5.13) follows from the definition, i.e. The property 3. (Equation 5.14) follows using the expression of the variance in Equation 5.12, i.e. The property 4. (Equation 5.15), i.e. the variance of the sum of two random variables is: where in the case in which there is no linear connection between and the covariance is zero, i.e. . Developing the computation of the covariance it is possible to prove property 5. (Equation 5.16), i.e. Finally, using the result in property 5. (Equation 5.16) the result in property 6. (Equation 5.17) follows easily:

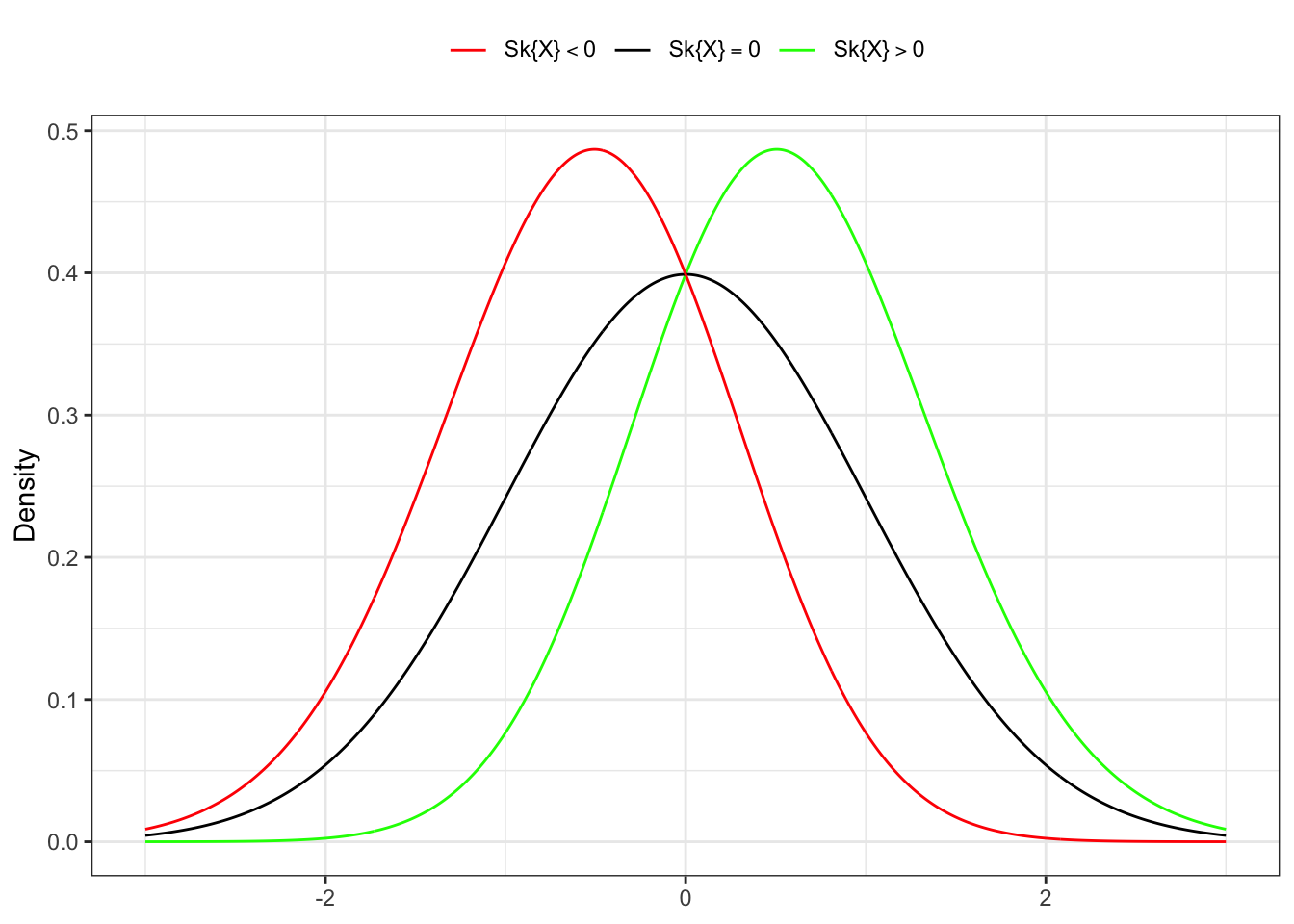

Skewness

The skewness is a measure of the asymmetry of the probability distribution of a real-valued random variable about its mean. The skewness value can be positive, zero, negative, or undefined. For a uni modal distribution, negative skew commonly indicates that the tail is on the left side of the distribution, and positive skew indicates that the tail is on the right.

Following the same notation as in Ralph B. D’agostino and Jr. (1990), let’s define and denote the population skewness of a random variable as:

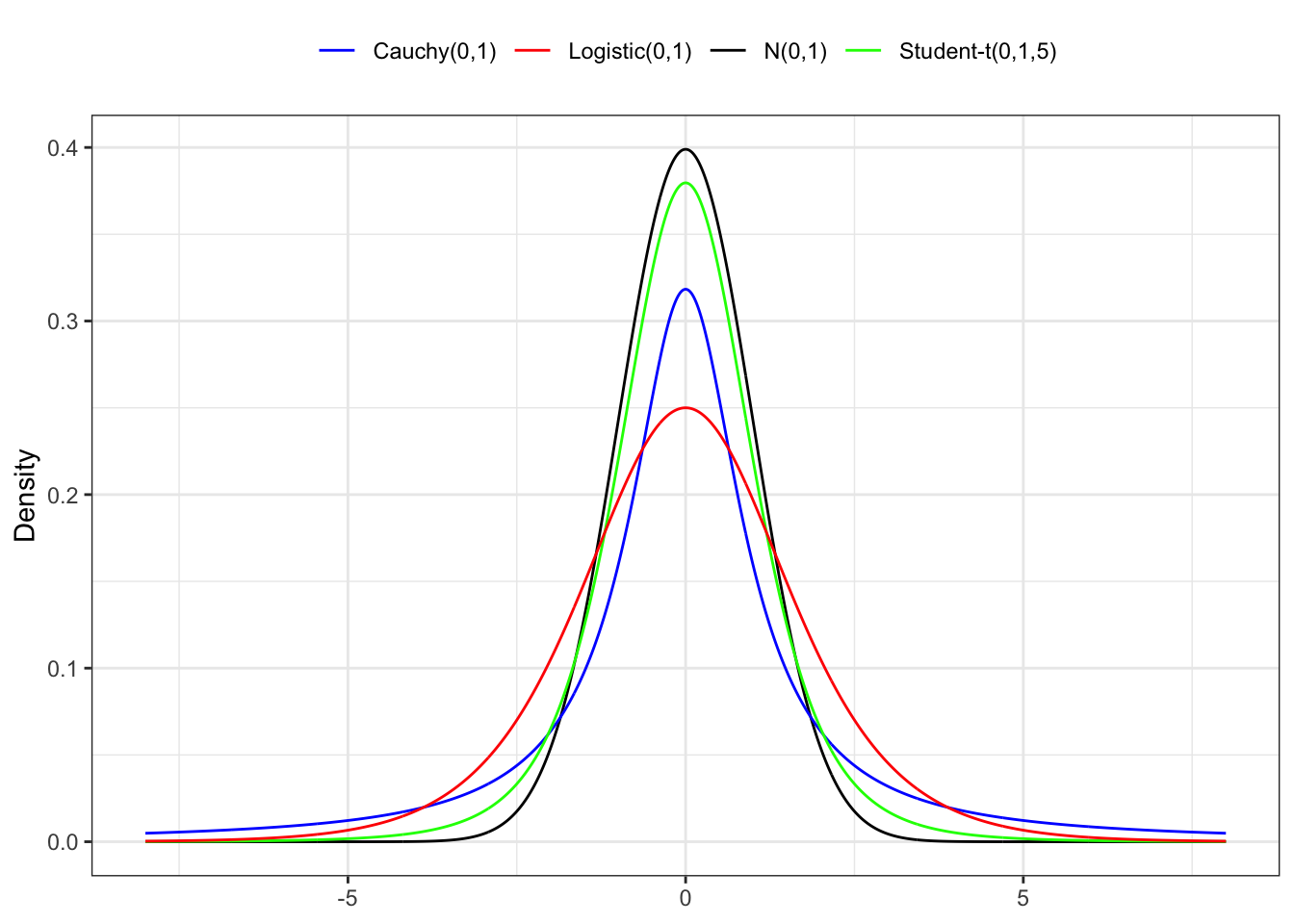

Kurtosis

The kurtosis is a measure of the tailedness of the probability distribution of a real-valued random variable. The standard measure of a distribution’s kurtosis, originating with Karl Pearson is a scaled version of the fourth moment of the distribution. This number is related to the tails of the distribution. For this measure, higher kurtosis corresponds to greater extremity of deviations from the mean (or outliers). In general, it is common to compare the excess kurtosis of a distribution with respect to the normal distribution (with kurtosis equal to 3). It is possible to distinguish 3 cases:

- A negative excess kurtosis or platykurtic are distributions that produces less outliers than the normal. distribution.

- A zero excess kurtosis or mesokurtic are distributions that produces same outliers than the normal.

- A positive excess kurtosis or leptokurtic are distributions that produces more outliers than the normal.

Let’s define and denote the kurtosis of a random variable as: or equivalently the excess kurtosis as .

Review of inequalities

Definition 5.2 ()

Let’s consider a random variable (Equation 5.6), then for all the Markov’s inequality states that Hence, this inequality produce an upper bound for a certain tail probability by using only the first moment of .

Definition 5.3 ()

Let’s consider a random variable (Equation 5.7), i.e. with first and second moment finite then for all the Chebychev inequality states that As with the Markov’s inequality, this one also produces an upper bound for a certain tail probability , but by using only the second moment of .

Definition 5.4 ()

Let’s consider (Equation 5.6), then the modulus inequality states that:

Definition 5.5 ()

Let’s consider two numbers and such that and let’s consider two random variables and such that: Then,

Definition 5.6 ()

Consider two random variables , i.e. with first and second moment finite, i.e. Then Note that this is a special case of Holder inequality (Equation 5.21) with .

Definition 5.7 ()

Let’s consider a convex function . Suppose that and , then if is concave the results revert, i.e.

Ralph B. D’agostino, Albert Belanger, and Ralph B. D’agostino Jr. 1990.

“A Suggestion for Using Powerful and Informative Tests of Normality.” The American Statistician 44 (4): 316–21.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.1990.10475751.

Resnick, Sidney I. 2005.

A Probability Path. Birkhauser.

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-0-8176-8409-9.